Amidst a swirl of global uncertainty, America’s economy is riding high into the new year, lifting investor expectations skyward. Our panel discusses what could propel (or derail) markets in 2025.

The U.S. is on course to achieve what few other countries have so far, emerging from the pandemic’s long-tailed aftershocks stronger than before. The cloud of inflation hanging over markets is slowly dissipating, unemployment is below historical norms, and markets have embraced the pro-growth prospects of deregulation and tax cuts. Yet for all the good happening in the economy, investors seem more than a bit anxious. Lofty expectations are often a recipe for volatility. A policy misstep by the new administration, a miscue by the Federal Reserve, or a self-inflicted fiscal crisis by a narrowly divided Congress—any one of these could send confidence teetering, if only temporarily. Will double-digit earnings growth be enough to calm nerves and keep markets barreling forward? To start off the new year, we’ve brought together experts from across the market spectrum, from the focused disciplines of technology strategies, small cap equities and insurance portfolios to the broad scope of public and private fixed income platforms and multi-asset solutions. For me, the key takeaway is that 2025 is setting up multiple ways to win if you know where to look. Hope you enjoy, and please feel free to reach out. |

Outlook: Starting from strength

Eric Stein: Let’s kick this off in the spirit of the New Year by focusing on what you’re feeling good about. What’s in store for 2025?

Barbara Reinhard: Coming off back-to-back years of 25%+ gains for the S&P 500, corporate earnings are accelerating, expected to grow by double digits in 2025. Even if those projections come down a bit, the economy is in good shape: Consumers’ finances are generally strong, net worth is up 12% since last year, wages are up 4%, and inflation is coming down. In the private sector, most corporations have termed out their debt until 2029, so it will be a while before refinancing becomes an issue.

I do think we’ll get more turbulence this year compared to 2024. The volatility in December helped shake out some investor complacency, but a lot of positive expectations around deregulation and tax cuts have been priced into the market since the election. The issue is, the U.S. already has one of the most deregulated economies on the planet, and it has one of the lowest corporate tax rates. Now, if House Republicans are able to marshal support for further tax cuts, fundamentals could get interesting, and if other countries follow suit, it could be a race to the bottom on corporate taxes.

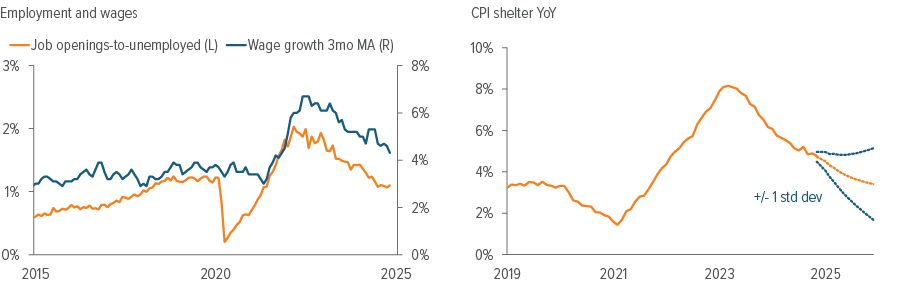

Sean Banai: From a fixed income perspective, the U.S. is a lot healthier than what’s going on in Europe or China. Our outlook for U.S. growth is a bit better than the market’s forecast, as innovation and deregulation lead to productivity gains, which should support credit fundamentals at a time when spreads are tight. Inflation should also continue to trend lower based on a rebalancing labor market and declining shelter costs. That will give the Fed room to continue cutting rates.

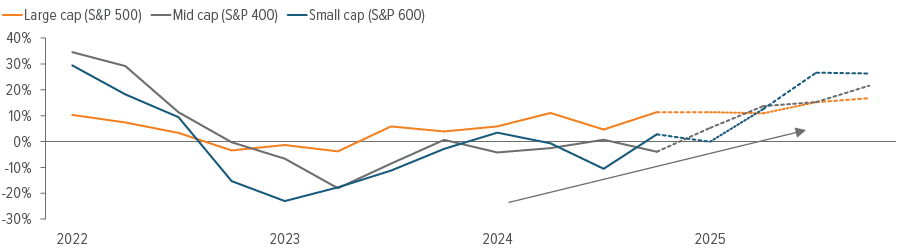

Michael Coyne: On the equity side, the market has decided that Trump is pro-growth. Now the rubber needs to meet the road in terms of how policies are implemented and in what order. Deregulation will increase market opportunities and improve profitability across a number of sectors including financials, industrials, technology and energy. For small cap specifically, the vast majority of economic activity in the U.S. comes from small and medium size businesses (SMB), and regulatory compliance is one of their biggest expenses. Reducing bureaucratic hurdles could deliver a meaningful benefit alongside low unemployment and less restrictive interest rates.

Stein: We’ve talked before about whether Trump would be good or bad for the technology sector. Erik, how are you handicapping the effects of various policies?

Erik Swords: I think tech will see more positives than negatives from policy changes. China tariffs are still a question. But if deregulation spurs more M&A, that alone could be a catalyst that’s been lacking during the Biden years. We’ll also see if Elon Musk’s influence could spur badly needed upgrades to IT systems across the federal government. The bigger story, though, is that AI evolution is entering a new stage that will open the door for a wider range of winners beyond the Magnificent 7 stocks. As the picks-and-shovels phase of building AI infrastructure continues, the next wave is beginning, which is the applications. You’re going to hear a lot this year about “AI agents.” These programs don’t just chat with you—they can understand context, make decisions and take action. This will be a game changer for automating tedious tasks, creating better customer experiences, speeding up software development, analyzing cybersecurity threats … the use cases are limitless.

The next stage of AI evolution is creating a wider range of winners beyond the Mag7.

As of 12/31/24. Source: FactSet, Bloomberg, Voya IM. Dashed lines are market forecasts

As of 11/30/24 (labor), 09/30/24 (CPI). Source: San Francisco Federal Reserve, Bloomberg, Voya IM. Dashed lines are market forecasts.

Stein: Thinking of how most consumers interact with AI, the experience seems fascinating but still in a beta test. You’re saying that’s going to start getting better.

Swords: People will start to experience the benefits, but it’s really about redefining how companies will operate—how they solve problems, manage costs or gain efficiencies. It’s not about customizing emojis.

Stein: Going in an entirely different direction, Chris, what’s your take on private markets in 2025?

Chris Lyons: The biggest trend is that the push into investment grade private credit will continue. In the traditional direct lending market—call it mid-BB to CCC—there’s so much dry powder that needs to be put to work. Unless merger and acquisition activity picks up and deal volumes increase, lenders will have to compete on spread and structure, which means a major shift to covenant-light deals. Partly because of this, a lot of insurance and pension investors have been moving to investment grade, where a new, higher-value section of the market has emerged.

Over the past few years, big private equity firms have been buying insurance balance sheets and using that stable capital to build businesses. They’re providing a base for highly complex transactions that weren’t feasible before, because you need huge anchor bids to get CFOs interested. With these “high-value-add” deals, lenders can charge a premium for being able to document and analyze complexity instead of taking on more credit risk.

Stein: What about infrastructure? There have been questions about how Trump’s energy policies might help or hurt. How do you see that playing out?

Lyons: I think things are moving in a positive direction for pretty much everything, except maybe offshore wind. Thermal plants will benefit over time from looser emissions regulations. Faster permitting will help both traditional and renewable projects get off the ground. Trump’s tone on renewables has softened considerably since the election, and his picks for key energy posts make it clear there’s room at the table for all forms of energy generation.

There’s a growing acknowledgement at all levels of government that we need to increase baseload power capacity to meet growing demand. Renewable energy is one of the cheapest ways to generate electricity, so even if there’s an attempt to reverse parts of the Inflation Reduction Act, such as expanded investment tax credits, it really won’t make a big difference.

Trump’s picks for key energy posts show there’s room at the table for all forms of energy generation.

Stein: Jeff, it seems lately that something interesting happens in the insurance asset management space minute by minute. What’s going on there?

Jeffrey Hobbs: Right, insurance is suddenly a growth sector. What we’re seeing is that the capital demand to support annuity growth is tightening the linkage between insurance companies and asset managers. The industry had $450 billion in annuity sales in 2024, which is roughly double pre-Covid levels.1 That’s partly driven by the move higher in interest rates since 2021 and partly demographic demand. To support that growth, the industry will need about $40-50 billion of new capital, and a lot of that is coming from private channels.

As far as broader market trends, here’s a telling relative value phenomenon: For the first time in any of our careers, the 30-year mortgage rate recently exceeded the High Yield Corporate Bond Index. It’s no wonder that a lot of non-bank residential lending has found its way onto insurance company balance sheets. That means insurers will touch consumers in a much broader way than simply through insurance policies.

Risks: Policy sequencing and the inflation threat

Stein: Pivoting to concerns, we’ll have more clarity on policy priorities after Trump’s inauguration. There are the pro-business aspects of an easier regulatory environment and lower taxes, but the other side relating to tariffs and immigration reforms could be inflationary. How are your teams approaching this issue?

Reinhard: I’m more concerned about tariffs than immigration. Mass deportations are unlikely given the enormous cost and the legal and logistical challenges, whereas the president can impose 50% tariffs without congressional approval. Tariffs are a hidden tax on U.S. consumers, which could depress spending power and raise concerns over potential stagflation. Aside from some external event, the one thing that could cause a market correction is that inflation forces the Fed to start hiking. As a result, corporate earnings get pinched, and you eventually get an earnings recession. However, I think this scenario is unlikely given the strength of global GDP growth.

Coyne: If what you describe happens, the end result is a consumer-led slowdown. Between Fed rate hikes driven by inflation and a consumer slowdown, the impact of each may be mitigated by the other. In that scenario, I’m not sure which one is the chicken and which one is the egg.

Reinhard: In that scenario, I think the chicken is the Fed.

Inflationary tariffs without pro-growth tax cuts and deregulation could be a concerning combination.

Banai: The sequencing matters. Changing regulations takes time, and tax cuts may not be the top priority right out of the gate, since most of the 2017 tax changes won’t expire until the end of the year. And if Congress only extends current tax cuts without lowering the corporate tax rate, there’s no net benefit. So if Trump starts with huge tariffs and deportation announcements at a time when inflation is already in the spotlight, that could raise alarms of fewer rate cuts and slower growth.

Stein: In other words, if tariffs and immigration come first, you get the negatives without the positives.

Banai: It’s a bigger factor for fixed income than equities, because credit spreads are priced for near perfection, so any perceived policy misstep could create some volatility. But at a fundamental level, the economy and companies are in good shape, and Trump has a way of floating policy ideas to see how markets react and then dialing back what’s actually implemented. If he sticks to that pattern, it should temper policies that might derail growth.

Lyons: You can carry the sequencing issue over to private markets. For two years now, people have been predicting that higher rates would trigger more defaults, because below investment grade companies often use floating-rate financing. So far, that hasn’t materialized. But if you get a sequence where tariffs drive inflation and rates higher— and then you don’t get the pull of earnings on the back end—those predictions of higher defaults could come true.

That’s more of a 2026 issue, though. Most credit agreements have a fixed-charge coverage test on a four-quarter rolling basis. If a borrower has two good quarters in the front, they wouldn’t be in default until next year. Even then, I think corporate earnings growth will keep the high yield market willing to refinance borrowers out of bad loans, which is what happened during Covid.

Stein: Let’s go back to the matter Sean raised about valuations. Markets are quite rich, almost across the board. How much do high expectations worry you?

Reinhard: The weight of the balance tells me that investor enthusiasm may not be at a major market top, but there isn’t much wiggle room. A few surveys are somewhat depressed, such as the Conference Board Measure of CEO Confidence and the University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment. But most other sentiment measures are pretty high, and institutional investors have very little cash on the sidelines. There’s no wall of worry for markets to climb, which isn’t the type of environment that’s likely to produce a repeat of returns from the last two years.

But stepping back, valuations are good predictors of longer-run returns. You have to be careful looking at a one-year time frame. There are a lot of positive fundamentals in place. What gets economies and markets into trouble is when consumers lose confidence, and that’s not happening.

What gets economies into trouble is when consumers lose confidence. That’s not happening at the moment.

Stein: Valuations are more of an anchor for fixed income, because spreads can’t really go negative, whereas with equities, price-to-earnings and other valuation metrics can stay rich for longer. Any other issues out there to raise?

Swords: Let me open a can of worms that has nothing to do with the economy. How do you control AI in a way that keeps it from going completely off the rails? Legislators are already struggling to keep up with the pace of innovation. Think of the debate happening over Section 230 and the liability of online platforms for user-generated content. That’s way less complicated than regulating autonomous vehicles or recursive self-improving AIs. Our system simply isn’t equipped to adapt fast enough to new capabilities or their implications for society. And even if we could get Congress to agree on something, how do we get to something resembling global cooperation on AI best practices when the battle for AI superiority is on the line?

Whatever your view is on the timeline for achieving general AI—and I think it’s years, not decades—there will be a period when human-level intelligent machines are making decisions and taking actions without consistent global guardrails in place. We’ll have to adjust to whatever happens.

Stein: You must be a hit at parties.

Swords: Depends on the party.

Opportunities: Capitalizing on market evolution

Stein: Now that we have the setting for 2025, what are you seeing that’s not super expensive? What opportunities are being overlooked?

Swords: One area that’s benefiting from AI growth, but with less demanding valuations, is cybersecurity. AI models need data to function, and keeping all that data safe will present new and complex vulnerabilities for cybersecurity firms to defend in the coming years. There are also some attractive software and internet companies that should get a boost from the progression of AI spending from infrastructure to applications and services. We’re also keeping an eye on some cyclical semiconductor stocks that are in a good position to benefit from improving IT spending and steady global growth.

Coyne: In small caps, assuming the 10- year Treasury yield doesn’t approach 5%, I’d give an edge to cyclical growth over secular themes. In this scenario, we’re looking for “earnings torque.” Companies whose demand was hurt the most by higher rates and thus stand to benefit the most from lower rates will see much higher financial leverage and thus stronger earnings growth. Opportunities like that exist across several industries, including capital equipment, semiconductors and household durables.

Banai: In public fixed income, the risk/ reward tradeoff is better toward shorter-maturity securities, as we expect excess return to come from carry. There is some value in parts of securitized credit, such as collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and non-agency residential. A stronger growth environment could reduce the perceived credit risk for underlying borrowers in CLOs, and deregulation could speed the return of banks as buyers of AAA rated CLOs.

Reinhard: Looking globally, one place I see meaningful value and multiple ways to win is Japan. They’ve broken the back of deflation and made progress on corporate reforms. Yet there’s been relatively little institutional or retail foreign investment, creating an opportunity as more investors catch on to this compelling growth story. And with the yen still weakening, the currency trend could be favorable as well if hedged back into U.S. dollars.

Lyons: With private debt, the opportunity isn’t specific to 2025. When you’re providing solutions to borrowers, there’s evergreen value in structural complexity. That’s true whether you’re talking about asset-backed finance, corporate debt, infrastructure debt or commercial mortgage loans (CMLs).

For example, if we enable a major sale and leaseback transaction for a public company, the company can continue to take the depreciation and amortization as a deduction, but they don’t have to pay for it on a cash basis. The solution puts debt off balance sheet and improves earnings per share—and because of that, we can charge a significant premium above the underlying credit risk.

Or take infrastructure. If we provide a structure that allows a developer to pre-buy solar panels and start construction without worrying about supply chains, we can charge a meaningful premium over the project’s long-term equity return.

Hobbs: That plays into what we’re doing from an insurance portfolio perspective— looking at ways to take diversifying sources of spread premia that aren’t simply public credit beta. That generally means privates over publics and, in public markets, securitized credit over corporate credit. We’re focused on adding flavors of asset-based finance, including fund finance and various consumer risks. We’re also looking at an expanding opportunity set in commercial real estate lending markets that are in an early recovery phase, compared with corporate credit markets that are mid-to late-cycle and priced to near perfection.

Stein: Thanks, Jeff, and thank you to all our panelists and to our readers. We’ll check back again in a few months to see how these ideas play out.

Undervalued ideas for 2025

Banai: Securitized credit—deregulation beneficiaries and pockets of value

Coyne: Industrials—cyclical beneficiaries with limited downside (e.g., capital equipment)

Hobbs: Asset-based finance—attractive spread-to-public premiums with good structural features

Lyons: Investment grade private credit—spread premiums from complexity, not credit risk

Reinhard: Japan—a play on continued global growth with multiple ways to win

Swords: Cybersecurity—next phase of AI growth with compelling value