Stocks and bonds have pulled back since the Fed clarified its commitment to fighting inflation. Despite volatility, we believe equities will stay within a broad trading range and not retest earlier lows. Rising yields, particularly among spread assets, should make bonds appealing compared to equities.

Highlights

- Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s Jackson Hole speech dispelled any notions about an imminent pivot toward moderating rate increases. Instead, he reaffirmed that the Fed is committed to higher rates for as long as it takes to bring down inflation.

- Even though Powell said nothing new or surprising, equities fell steeply, raising questions about how much further they might fall as financial conditions tighten.

- Equities could take another leg down if earnings weaken, though with expected economic slowing in 2023, rates are not likely to drive a further equity pull back or cause PEs to decline.

- The bond market reaction to Powell’s speech was not as severe; yield spreads didn’t change much and the long end of the U.S. Treasury curve was fairly stable.

Closing the books on a secular trend

The transition from the era of steadily falling rates and low inflation has been underway for some time. Yet, the emergence of a new regime hasn’t seemed that pronounced until the last year or so, as the impacts of the Covid pandemic have faded. In recent years, because inflation still was not a threat, the Fed was able to focus on unemployment and could quickly pivot from rate increases back to rate cuts. This time it’s different: with inflation seriously rising priorities have changed, and the Fed is focused on keeping inflation expectations from becoming entrenched in wage and price decisions.

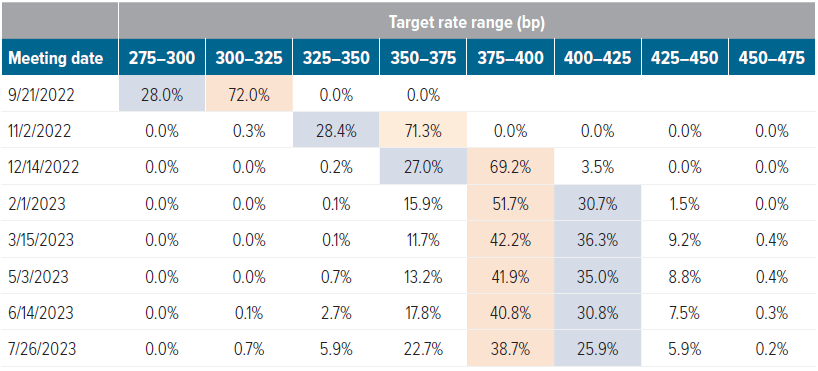

Labor market weakness and economic slowdown are unlikely to prompt a policy pivot unless inflation significantly decreases as a result. As Powell noted, collateral damage to businesses and employment “…are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation.” Expectations remain in place for a 75-basis-point (bp) rate increase in September, with six more hikes through March 2023, a first rate cut in November 2023 and a second cut in January 2024.

Source: CME Fedwatch; orange = highest probability, blue = second highest probability, data as of 9/2/2022.

Signs of slowing are gathering. The second reading of 2Q22 real GDP improved from –0.9% to –0.6%, though still showing contraction for a second straight quarter. The improvement was largely due to an upward revision of consumer spending, which bodes well for the economy but could embolden the Fed to keep raising rates.

The yield curve remains inverted. In recent weeks, the two-to-ten spread has been negative but fairly stable, ranging between –20 and –40 bp. August nonfarm payrolls added 315,000 new jobs, a pullback from July’s 526,000 pace while still pointing to labor market tightness, as the unemployment rate rose to 3.7%. August CPI data will come out ahead of the September FOMC meeting, but without a dramatic downshift are unlikely to alter the rate decision.

While the Fed and other central banks are committed to bringing down inflation, a quandary surfaced at the Jackson Hole symposium as to how much inflation can be trimmed before the economic and social pain becomes unacceptable. Consensus seemed to be that inflation could be brought down to around 3% without too much disruption, but that going from 3% to 2% would greatly increase recession risks and inflict too much pain on the lower income quintiles of the population, who shoulder the brunt of the impacts from weaker labor conditions and higher consumer prices.

Also, certain short-, intermediate- and long-term trends point to a higher cost economy in the months and years to come. Until a new equilibrium is established, bringing inflation down to the Fed’s 2% target could be challenging.

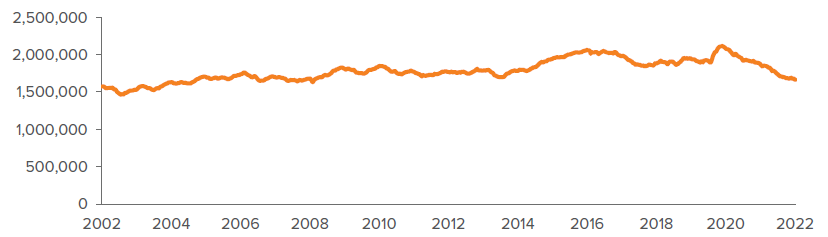

In the near term, crude oil markets have shown an atypical dynamic this year that likely will increase prices during heating season. Typically, in the first half of the year as the weather warms, drawdowns slow and supplies build. This year, sanctions against Russia for invading Ukraine have disrupted supply and led to net 1H22 drawdowns — supply will be lower as heating season begins.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, data as of 8/31/2022.

Over the likely span of the current rate cycle, manufacturers seeking to mitigate their vulnerability to global supply-chain risks will be adding onshore capacity, which likely will entail higher labor costs. Eventually, those costs should be mitigated as greater supply certainty leads to more investment in productivity enhancing technology, but cost pressures could prove sticky while the Fed is in tightening mode.

Longer term, housing costs have put home ownership, and even renting, out of reach for many recent entrants into the workforce. In June, higher mortgage rates made homeownership less affordable and slowed home price growth. That could help ease inflation, but also could push up rents. Later, as younger cohorts seek to build families, they could reignite home price pressures.

Earlier in the third quarter, some investors began to believe the Fed’s aggressive rate increases were done and that, starting in September, the Fed would reduce the size of hikes before cutting rates in 2023. Those beliefs spurred an equity market rally that for a time seemed poised to recoup year to date losses.

Powell’s speech dispelled the notion that the Fed might soon moderate its policy stance, and set the stage for an equity pullback, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average falling about 1,000 points. While the equity market reaction was intense, it aligned with historical precedent. In market-bottom episodes since 1922, bear-market rallies have averaged 16% before pulling back. The most recent market rally reached about 16%, and thus represented a likely retracement point.

Stock investors may be shifting to a “good news is bad news” mentality, in which good economic news is seen as a harbinger of bigger Fed rate hikes. For example, recent JOLTS data, which showed the labor market remains tight, prompted another equity pullback. Despite volatility, we believe equities will stay within a broad trading range and not retest earlier lows. Equities could take another leg lower if earnings weaken, but for now fundamentals seem intact and imply market resilience.

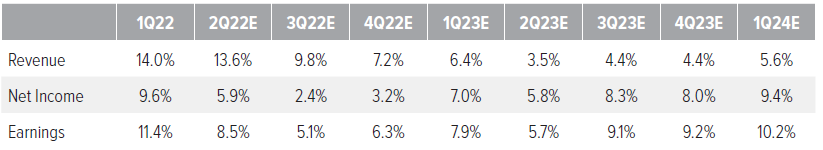

Source: I/B/E/S data from Refinitiv, as of 9/2/2022.

As of September 2, 2022, Refinitiv estimated 2Q22 S&P 500 earnings to have grown 8.5% year over year, with 5.1% expected for 3Q22 and 6.3% for 4Q22. Sector earnings estimates ranged widely, with an average of seven of 11 sectors expected to deliver positive growth in each quarter. Forward PEs had adjusted; the 12-month forward PE was 17.1, down from 18.1 in August. If economic growth slows as expected in 2023, then we would expect real yields to fall, which makes it less likely that earnings multiples will decline significantly.

Fixed income outlook

Bonds did not react to Powell’s speech as severely as equities did. Early in the following week, there was some “bear flattening,” i.e., shorter maturity yields rising faster than longer maturity yields, but the long end of the U.S. Treasury curve remained fairly stable. In our view, rates are not likely to cause a further equity pullback. The equity shakeup following the speech didn’t change yield spreads much; investment grade credit spreads widened only about 8 bp.

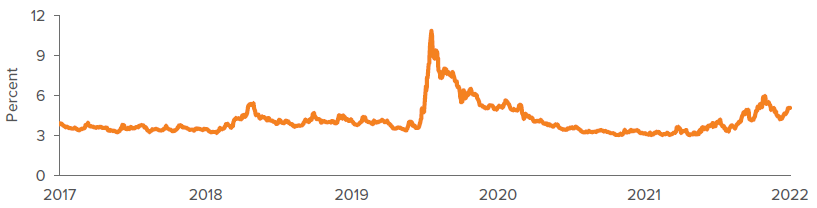

Shorter-term Treasury yields are likely to increase as investors reassess how high rates could go. Generally, higher yields should make fixed income strategies more appealing compared to equities. Equity weakness has not yet impacted high yield credit spreads, which recently moved from near 500 toward 600 bp. We expect spreads to remain volatile but not exceed 800 bp.

Source: Ice Data Indices, LLC, ICE BofA U.S. high yield index option-adjusted spread, retrieved from FRED, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/ series/BAMLH0A0HYM2, September 6, 2022. The ICE BofA Option-Adjusted Spreads (OASs) are the calculated spreads between a computed OAS index of all bonds in a given rating category and a spot Treasury curve. An OAS index is constructed using each constituent bond’s OAS, weighted by market capitalization. The data represent the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index, which tracks the performance of U.S. dollar denominated below investment grade rated corporate debt publicly issued in the U.S. domestic market. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

Rate volatility is likely to remain elevated; the ten-year U.S. Treasury yield has been ranging around 3%. At this point, ten-year rates are being driven not just by Fed policy but also by inflation expectations in Europe, as we saw in mid-August, when a surge in German PPI pushed up U.S. yields. With a Eurozone recession looming, the European Central Bank may not have the Fed’s latitude to tighten rates policy. This could make Europe another source of inflation pressures to which the Fed will have to respond.